Oceanic Decolonization - Coast of West Africa (2045)

We are listening to an episode of Ubuntu Talks, a pan-African political affairs podcast hosted by Coura Bangura. Today, Coura will be speaking with Beyan Boakai, a previous master fisherman for Liberia and now representative for the West African Fishing Fleet, about his fight to reclaim the fish and fisheries infrastructure of West Africa.

Welcome to Ubuntu Talks, this is Coura Bangura. Today I am speaking with Beyan Boakai, the representative of Liberia for the West African Fishing Fleet, a coordinated fleet operating in our common EEZ, now celebrated across West Africa for his leadership in the fight and struggle to reclaim our fisheries and oceans. Welcome, Mr. Boakai.

Beyan: Please, please call me Beyan.

Coura: Beyan! Terrific to have you in the studio today. What a journey the past few years have been for you, and now here back in the studio with your battle seemingly won. How are you? How does it feel?

Beyan: Honestly… It still feels unfinished. I am happy, ecstatic, about our ability, together with our friends in Mauritania, to reclaim Nouakchott last week, but I know the war is not won. There is still a lot of infrastructure that needs to be reviewed, also within the offshore oil and gas fields many of which are at least partially foreign-owned due to loans the government could not pay off.

Coura: I see, I see. It seems a much longer process than many of us would have fathomed when this conflict first became apparent… I remember during your last visit to our studio a few years ago now how relieved I was after there was finally a halt to the warfare at sea and a return to some sense of normalcy, but you were quick to tell me the battle was not over then either. Did I get that correct?

Beyan: That’s right. Once we had reclaimed our oceans, pushing foreign trawlers out of our inshore exclusion zones and expanding those, it dawned on us that the revenues from our resources will continue to go to others, far away, if we do not reclaim our infrastructure. Our ports, processing factories. This realization, then, started off the process of what my wife called fisheries lawfare, and this is definitely an ongoing battle. But we are feeling very positive after our friends in Mauritania won back Nouakchott.

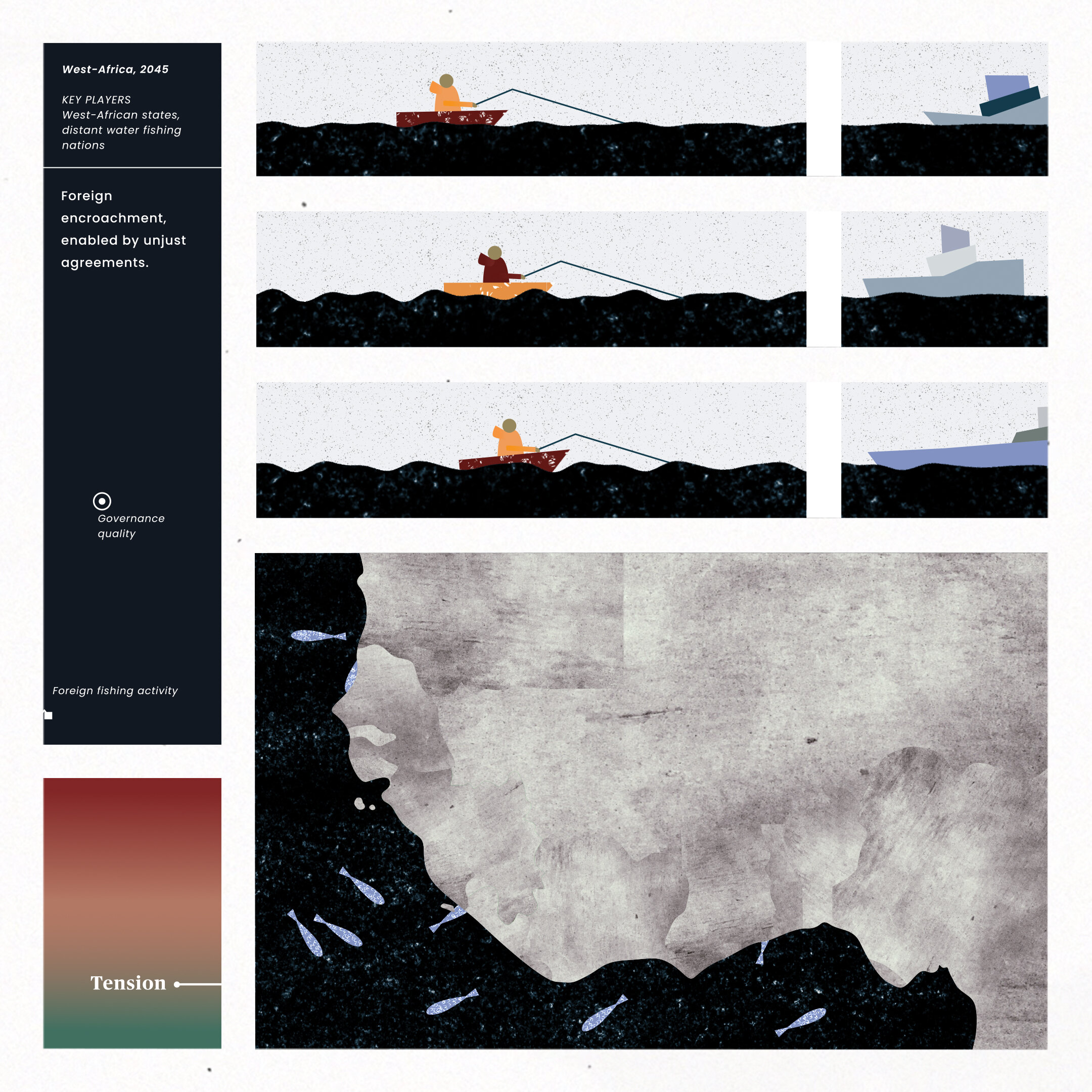

Coura: If you will, let’s start from the beginning, before the conflict erupted. Back then, of course, foreign vessels fishing in our waters was described by many as a win-win situation. A situation where both West African countries and distant foreign water fishing nations would benefit. What did we not understand at that time?

Beyan: Well of course this was described as a win-win situation by our government, and governments in many neighboring West African countries at that, including Mauritania. Generating desperately needed public revenue, delivering skills and technology for access to our rich waters. All of this back then, seemed like a dream to many of us who were struggling to keep our heads afloat, quite literally.

Coura: But, even at the time many people, including the international community, could sense problems ahead.

Beyan: Yes. But our own governments were too busy enriching themselves off the deal. There was significant money in the licensing fees, export fees, which basically all went straight into our government’s personal pet projects and rumor has it, offshore accounts. I mean, the China Africa Fisheries Union was an entirely Chinese-run organization even back then, chaired by local chapters of transnational, state-owned fishing companies. There was no real engagement with our local fisherpeople, the deal was done above our heads really. Many nations profited unfairly from our marine resources. Spain, Russia, China, South Korea… All were able to loot our oceans and feed their farmed fish off of our backs for many years. We lost billions of dollars each year. They did not only exploit our fisheries, but also our people… The horrendous conditions in which our people had to work aboard these foreign vessels, all for cheap fish… And the number of foreign boats just kept increasing. Until, of course, our movement to decolonize our oceans started.

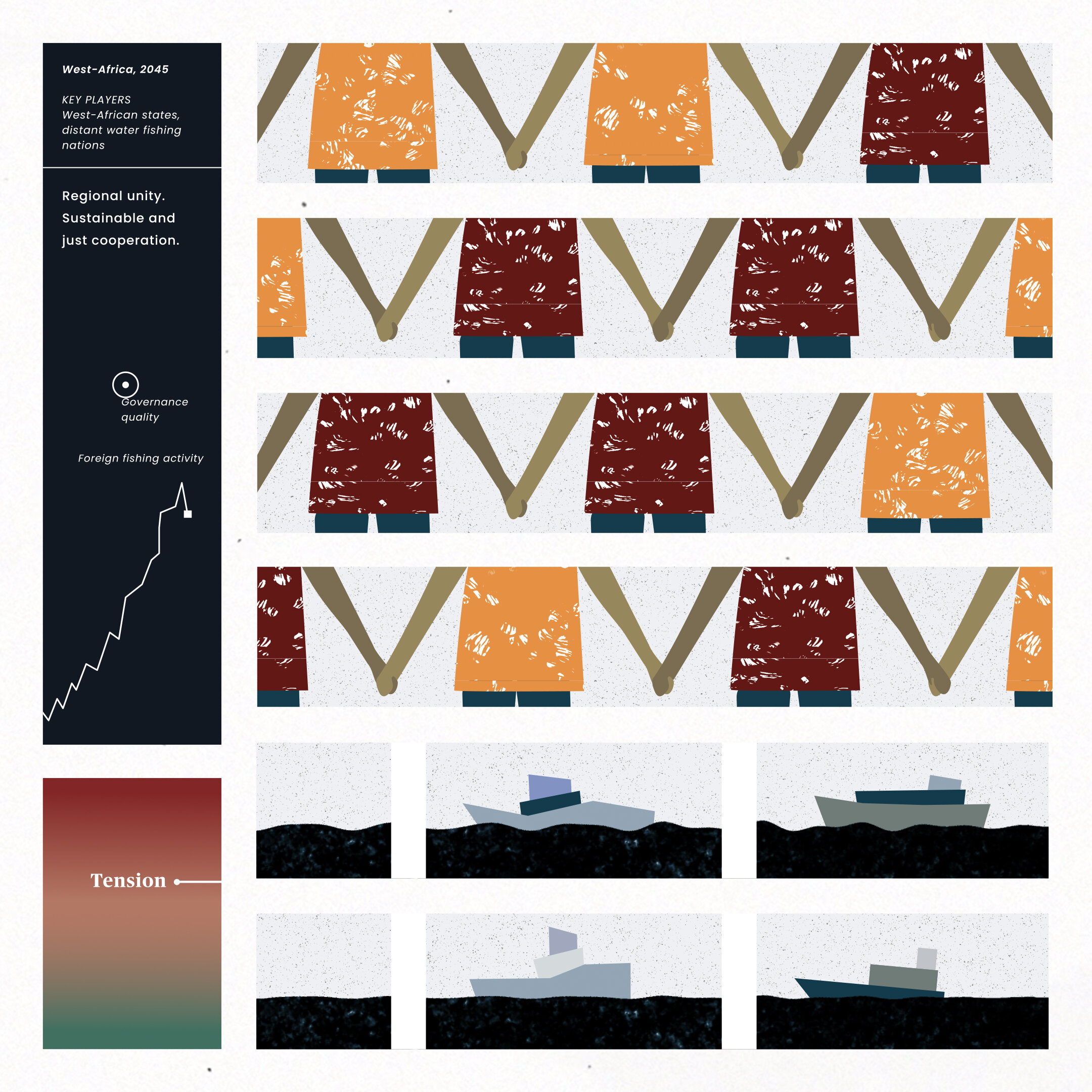

Coura: Right. Why do you think it took so long for West Africa to band together against this almost hostile, neo-colonial take-over of our oceans?

Beyan: Well at the time there were other, bigger issues, right? Some of the issues had been brought forward by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission in 2015, but not much was done. Renewed political conflict, economic instability, the Ebola riots,... Our region was preoccupied. The African Union was instrumental in ending such violence, brokering the necessary peace throughout ECOWAS - which was truly a turning point. If the Union had not expanded and confederated, as well as granting greater power to ECOWAS, we would never have been able to band together through unions, an important connector from the onset being CAOPA, the African Confederation of Artisanal Fishing. It really helped that a new generation took over the leadership of the AU and had a genuine, grounded vision for regional unity. It laid the foundation necessary for small unions, CAOPA and other partners to rise up. Remember, this has not only been a fight to reclaim our fish and infrastructure; but also to fend off other unsustainable maritime industries such as the expanding oil-and gas industries claiming our fishing spaces, and to finally develop beyond our national capacities to create a modernized fleet across the region and expand into deep-sea aquaculture.

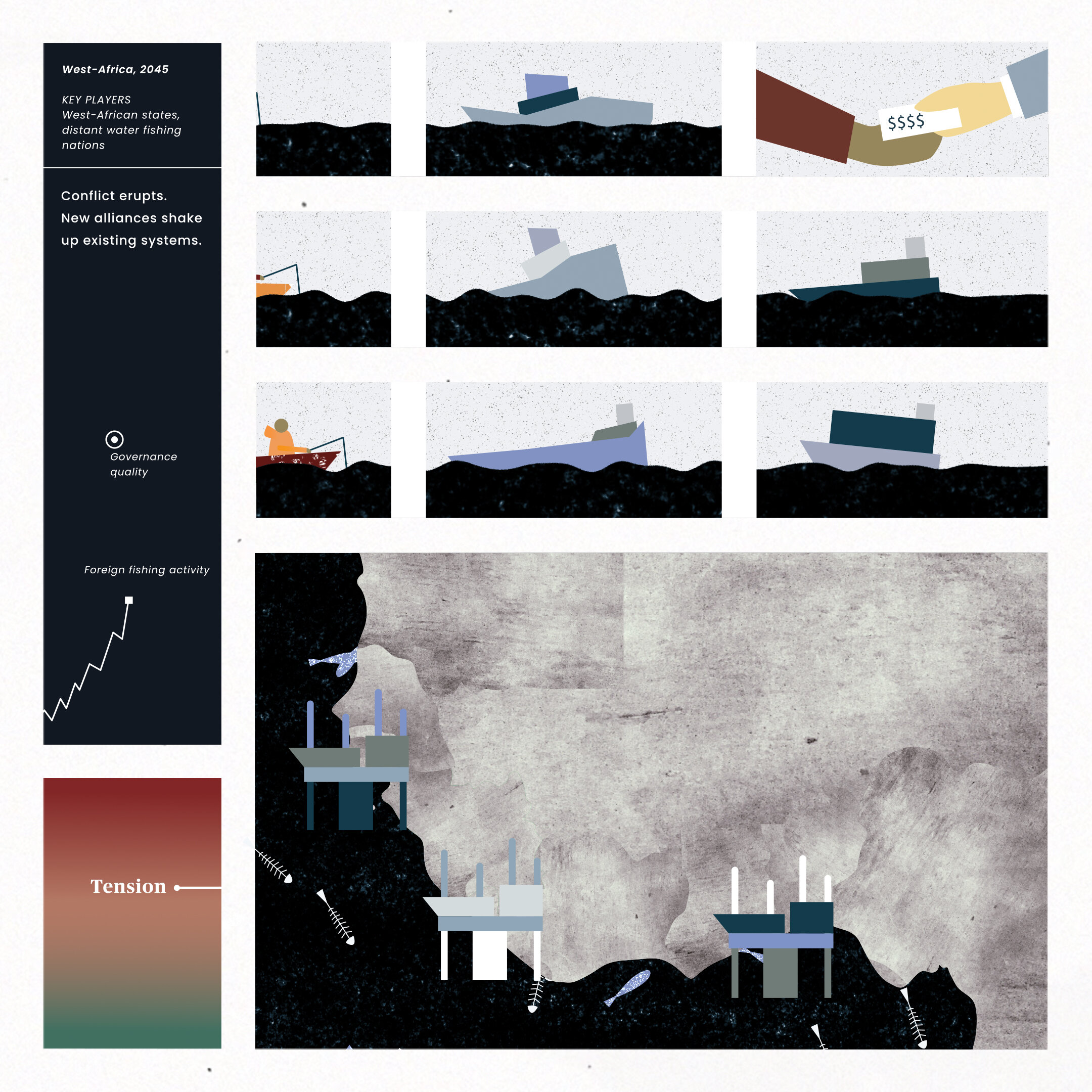

Coura: Right. But first, let’s go over your recollection of this revolutionary conflict once again for our new listeners. What do you remember most of that turning point, the period when this volatile conflict erupted with the Chinese, South Korean and Spanish boats in particular?

Beyan: Well. I was leading the fisherpeople on my Yongoro 6 at the time. We all had had enough for a long time already. For years we could not gain access to our own fishing grounds, occupied by enormous, hulking mothership trawlers and their fleets of buzzing smaller boats posing as small-scale fishers. We were forced to buy back fish landed by international vessels at 5 times the price. Out of frustration the rebel movement grew, with some fisherpeople setting up headquarters on a rusty, decommissioned oil rig. We had already teamed up with the vigilante Sea Wolves to make a stand and push away these vessels from our coasts, but many of us were losing patience. It was honestly feeling like a losing battle because we knew our rebellion would never make a difference as long as these access agreements existed, as long as foreign investments dominated our infrastructure and our resources. Ports, processing factories, fish markets… So many of it was foreign owned, often because our governments were not able to pay of the loans they had signed. Foreign investors knew this, they lied to us, they took advantage. At sea and on shore, we were treated as the outlaws by our own governments! We were forced to confront our own Coast Guard as they turned against us, paid off by our politicians and foreign investors.

Coura: And then the first shots were fired…

Beyan: Yes. Despite the months’ long tensions in the area, and on-and-off clashes between vessels, I had honestly not felt it coming. It is still difficult to talk about, also because what actually happened remains controversial and we are still dealing with the repercussions in court. But it had started earlier that week with a stabbing leading to the death of a local woman, Mariama Sesay, a much-loved fishtrader, over the prices charged by the colonizers for our own fish. Those had skyrocketed not least because of overexploitation, but also because of greed. There was such a desperate hunger for high-quality protein globally, everything good was exported and the scraps offered to us at exorbitant prices. It was the stabbing of Mariama that led a group of fisherpeople to retaliate at sea. This is when shots were fired late at night. No one knows exactly how it all started… There is evidence that it was the Coast Guard that shot first, at our own vessels, protecting foreign interests at the direction of the fisheries ministry… I was immediately informed through radio, and set course to the area right away. I was stopped by the Coast Guard, detained. Beaten. Tortured. (a deep note of sadness in his voice) In just 24 hours we had lost 21 fisherpeople. One confirmed Spanish death. Those numbers tell the real story, I think.

Coura: More lives were lost over the course of those three weeks, while you were detained.

Beyan: It was excruciating. I was not kept informed, was not allowed to attend the funerals of those in our community. They had no grounds to keep me detained, it was chaos.

Coura: Things quieted down after those three weeks of on-and-off violence. What happened?

Beyan: I was released, eventually. I came back to thousands of messages, phone calls, of disgruntled, angry, scared fishermen from all across West Africa. I felt it: this was our time. But we had to avoid violence, we had to be smart. Use the tools of the colonizers against them. Not in the least because we knew we did not have the means to win this war on the water. We quietly, but powerfully, revolted, engaging with partners mainly through CAOPA as a platform. Many CAOPA members stopped engaging with international vessels, traders, processing facilities. Foreign products were boycotted. It had a ripple effect across the world: The ICIJ, ProPublica, and CENOZO investigative media alliance had campaigned across the west to raise awareness, raise the alarm. The news spread like wildfire and became known as our ocean decolonization fight.

Coura: Under this mounting pressure, things started to change for the better.

Beyan: It took a long time. After months, we finally had some politicians fighting for us, partially thanks to help from an increasingly stronger African Union which put pressure on individual governments, but mainly thanks to our strong fisherpeople. The Coast Guard was called back and told to show restraint, and more naval vessels were made available to enforce our West African Exclusive Economic Zones, in part supported by the U.S. Africa Command’s Security Cooperation program. Slowly but surely, most of the foreign vessels retreated under the mounting pressure. But, they still basically owned our facilities and, when criticized, said they were acting under the law.

Coura: That’s right! After the infamous violent clashes at sea, you came to our studio the first time together with your Sea Wolves partner, explaining the physical fight might be over, but that indeed we were far from claiming back our ocean resources.

Beyan: My wife was the first to make me aware. She is the brains behind that second phase of our ocean decolonization strategy. We had to kill the unfair access agreements, reclaim ownership over our fishing ports and fish processing factories. And we also want to stress that we are not against all foreign investments or partnerships! But it needed to be to the benefit of West Africa as well. The community, the fisherpeople, needed to be consulted and benefited. Fighting for transparency within fisheries access agreements between governments as well as big foreign companies and our governments was the first step. Many of them had only been established due to the shortsightedness, or sometimes outright corruption amongst our politicians. We fought for the renegotiation of those access agreements and only establish new ones if both parties were on equal footing. My wife led this with success: Liberia is now in the process of establishing an international investment treaty with foreign interests, not only within fisheries but also other maritime industries, informed by local communities through consultation rounds. Transparency obligations and mandatory reporting will be included. We are even striving to make the reporting of beneficial ownership obligatory so no foreign-owned companies can front as a West-African enterprise. (pauses)

My wife… She was fearless despite all the threats we were getting. You know, we had to work underground, off the grid, for months because of the possibility of retaliation against our family.

Coura: But now, months after this lawfare process as you call it had started, you have won some battles and with the recent reclaiming of Nouakchott, you feel optimistic?

Beyan: Yes. Now our politicians are finally treating the fisheries industry as what it should have been all along: the lifeblood of West Africa, an engine for our future prosperity. It is this political support that makes me optimistic. We can finally invest in our future. Within the African Union we have created a shared quota system, allowing for greater flexibility and efficiency, and we increasingly reinvest profits from our fishing industry in aquaponics and community deep-sea aquaculture, creating more jobs. These facilities in the open ocean are really our future. Gaining our fishing grounds and ports back was an important step to free ourselves from exploitation, but we now know that aquaculture is an important part in securing nutritious food for generations to come.

Coura: Amazing. Thank you Beyan, for your inspirational work, and continued fight in reclaiming our ocean resources and beyond. An honor to have you back on Ubuntu Talks.

Alternative pathways

West African governments try to squeeze as much revenue out of already overexploited fisheries as possible. Rural fishery communities feel the pressure and continue to struggle. Urbanization pulls young people from the communities to cities, where more profits can be made. Fishing activity slowly declines and the system grinds on at a bio equilibrium (when the number of individuals being removed is equal to the population growth rate). Fisheries dwindle, becoming less attractive even to foreign fleets as they are no longer profitable.

China shifts its food security strategy and offers West African governments to stop harvesting fish in the area with their own vessels in exchange for exclusive sourcing agreements to feed their growing population. China would focus on processing and exporting fish harvested from West Africa and pull out its trawlers from the region. This, however, negatively influences local food security as it drives up fish prices in West African markets.