Polar Renaissance - The Arctic Ocean (2060)

This is a speech by Sardana Nikolaev, CEO of Sakha Fishing and chair of the indigenous-business partner organization ‘Polar Renaissance’, held during the fifth anniversary of the Arctic reconciliatory meeting. All Arctic Heads of State are present for this meeting at the Arctic Council – from the United States of America, the Russian Federation, the Kingdom of Denmark, Canada, Iceland, the Republic of Finland, The Kingdom of Sweden, and the Kingdom of Norway - to further strengthen Arctic cooperation.

Sardana: Today I am here to celebrate with you all. A celebration of our renewed international Arctic cooperation. No so long ago, we were on the brink of conflict, so standing here in front of the Arctic Council, with all Heads of State present, feels like a true victory. I am speaking today not only on behalf of my fishing company, Sakha Fishing, but also on behalf of ‘Polar Renaissance’, a pan-Arctic initiative by indigenous business leaders that is passionate about the Arctic, its people and its future. I want to start by reminding us all why our Arctic unity, though still fragile, is such an achievement.

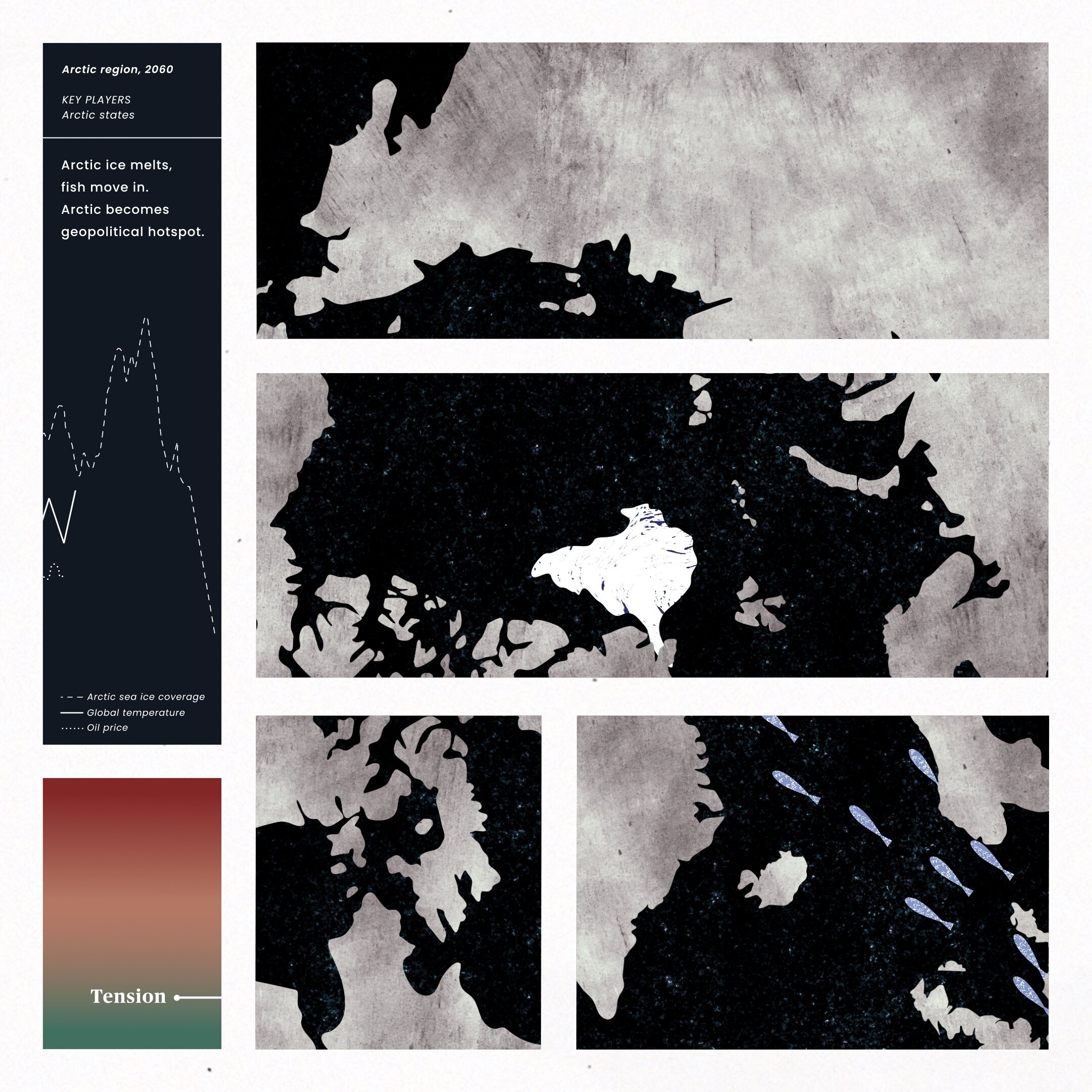

When I was young and not yet the business owner I am today, Russia was still ruled by Putin, and had long ignored (pauses)… Well, with apologies to my Russian colleagues in the room, basically welcomed some of the consequences of climate change and ocean warming. The disappearance of the sea ice in the Arctic in particular was embraced by our politicians. It was much more rapid than any of us expected, of course. My Yakut ancestors, humble fisherpeople surviving mainly on whitefish catches, were initially wary of the changes that came so rapidly. We started experiencing near ice-free summers much more quickly than any models had suggested... (sighs). Despite this, few Russian politicians took seriously the disastrous consequences of these changes. The Yakut people were some of the few, together with some lone scientists, that witnessed first-hand some of the pervasive changes Siberia at large was undergoing: thinning sea ice, flooding, thawing permafrost, changing migration patterns of land and sea animals. Their concerns were dismissed. Our government and many Russian businesses, from fishing to mining to energy companies, instead saw a new gold rush. They thought that, at worst, some of the adverse effects of climate change such as the wildfires we already saw intensifying, could surely be managed. The promise of the Northern Sea Route, the trans-Arctic shipping routes, all the resources that would become available… The chance to build a “new palace”… it was all too good to pass up. Our government took advantage, started subsidizing new technologies and ocean businesses with the help of other interested nations from the East, and pushed into the Arctic, both economically and militarily. Planning for new seaport facilities, reconditioning abandoned Soviet military bases, mining operations, oil and gas pipelines and, of course, fishing ports and processing facilities. One funny story, at least in hindsight, was the hysterics and extreme absurdity as a Canadian Coastguard contingent and an American navy strike force led by a weaponized icebreaker, squeezed past each other while navigating the narrow and still treacherous Northwest Passage. During this time, the cooperation achieved by the Arctic Council had already started to erode.

Parts of Siberia, and indeed many historically remote areas inhabited by indigenous people all over the Arctic, saw businesses rush in. Older generations of fisherpeople in Yakutia were weary, but, similar to many Inuit and Yupik people in the American, Canadian and Greenlandic Arctic, we had been grappling with the loss of traditional livelihoods and high rates of unemployment for decades. Community elders witnessed more and more young Yakut people being drawn in by the economic boom. Young Yakuts hoped it could provide some stability in an environment where the weather became less predictable, where sea ice was unstable and traditional fishing and hunting much harder to maintain. They were promised a ‘New Era of Prosperity´ by the government. It drove them to leave behind family businesses and start working for large fishing companies, in new fish processing facilities, or other maritime industries; back then none of them led by indigenous people. I became one of those young Yakuts searching for an opportunity.

To my community and I, it seemed great for a few years, mainly because we were not aware of the ongoing political tensions or environmental destruction. We know now that any journalist or whistleblower coming out against the government was quickly silenced. Yet all industries were grappling with the consequences of tensions in the changing Arctic soon enough. The oil and gas industries were first. As the retreating sea ice revealed more and more untapped fossil-fuel resources all over the Arctic, political and eventually military tensions between Russia and Norway over competing interests in the Barents Sea soon made the sector unstable. Russia had made clear, by running aggressive military exercises that it would not share the oil resources found in the north Barents Sea, though Norway initially claimed part of it. Under pressure from its domestic politics that were distinctly anti-fossil fuel, Norway eventually backed down, and Russia thought itself unchallenged to claim these resources…

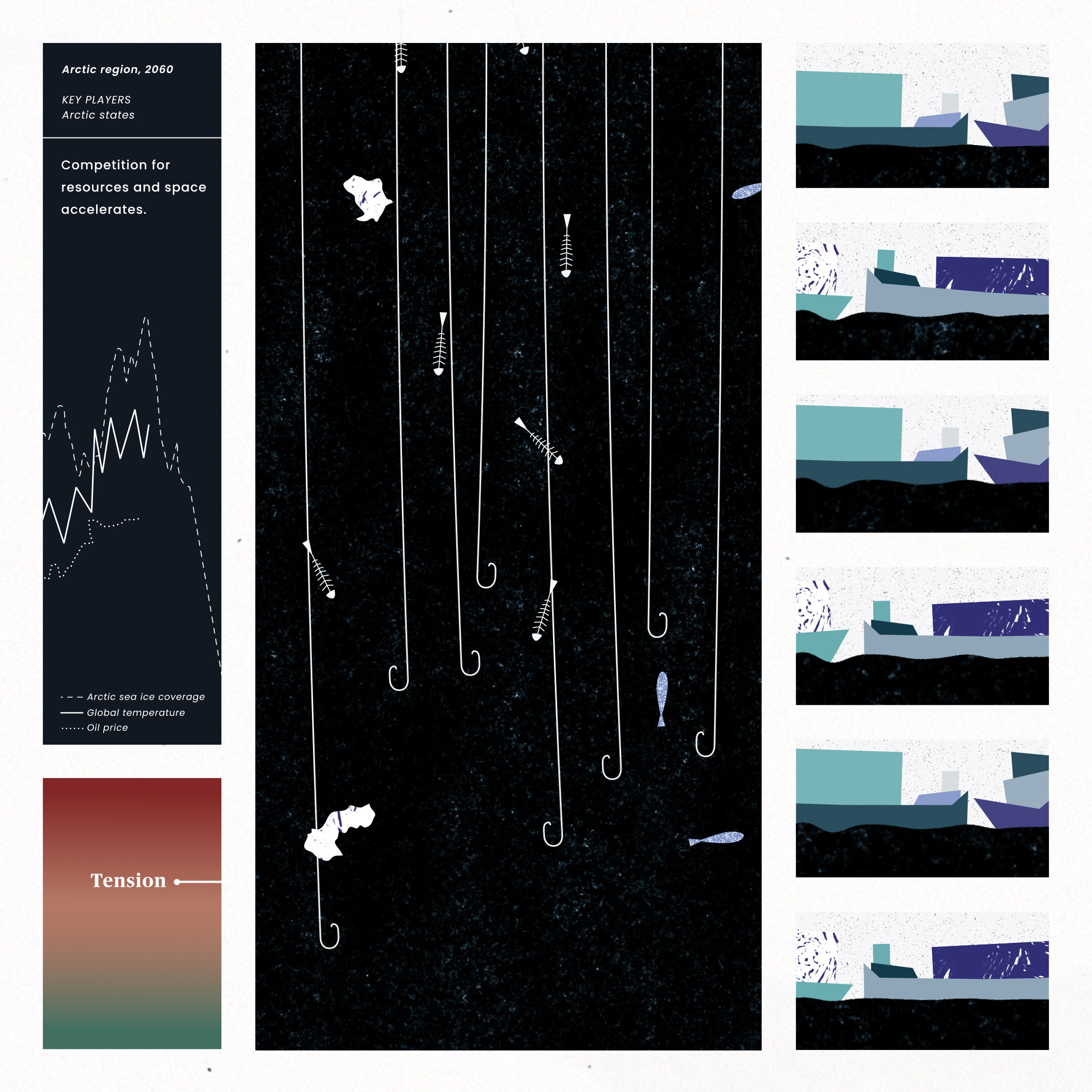

Also within the fishing industry, this is when I first started in the sector, executives seemed initially excited about changes to the Arctic ecosystem: the continuous increase of boreal fish predators such as cod was welcomed as a gift. But after the regulations on Arctic fishing were officially abandoned in 2034 and the fiction of exploratory fishing was exposed for what it was, everyone suddenly had fishing vessels in the Arctic, and illegal fishing was rampant. The influx of new species continued, but so did the influx of commercial fishing vessels, from all Arctic states. Without any legal framework, there was not much any country could do. An exponential increase in competition for Arctic fish created tensions in the area between fishing fleets. This is when I first became aware of just how politicized and dangerous the business I was in was becoming without a rulebook to guide us. The danger became particularly tangible when Russia assigned next generation naval vessels to accompany our boats to scare off competitors, occasionally ramming boats. Sometimes Chinese vessels were employed to accompany our fishing boats, keen to protect the investments Beijing had made in the Russian fisheries business as part of their Polar Silk Road plan. It all culminated in a near month-long stand-off just outside the Norwegian Exclusive Economic Zone, where Norway had detained four vessels that, allegedly, had made incursions into the Norwegian zone. Three of the vessels were Russian-flagged, one Chinese. Russia and Norway came close to military conflict at that time...

(pauses)

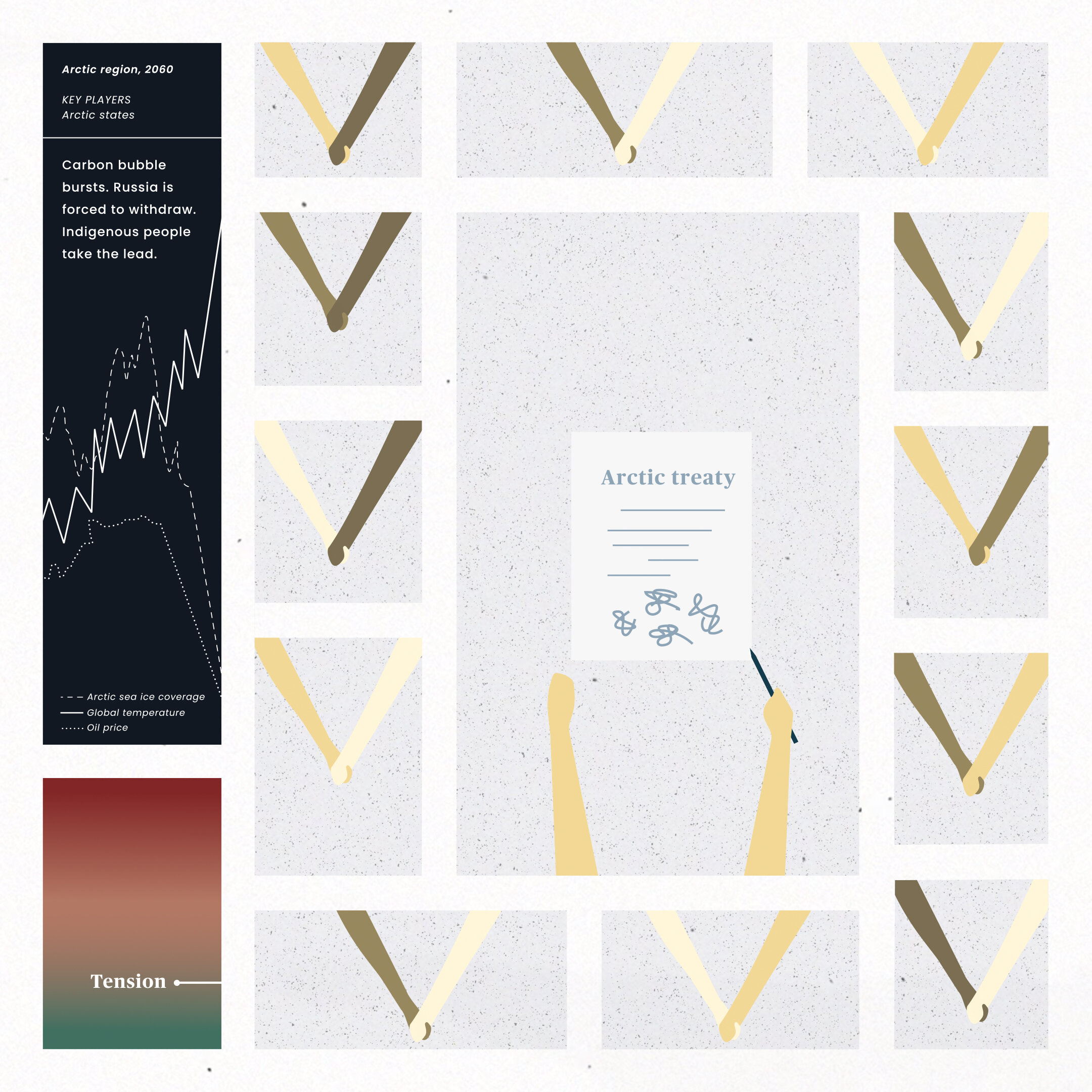

‘POP’! Then the carbon bubble burst. Oil and gas prices collapsed to precipitous lows almost overnight. This happened much, much faster than economists were projecting. The European central bank, followed by a large number of pension funds and other institutional investors, rapidly divested from all fossil fuel assets in an unstoppable cascade. Insurance companies stopped offering coverage for oil and gas exploration, and simultaneously two international oil companies announced plans to completely transition to renewables. The era of fossil fuels was over… Again, apologies to my Russian colleagues, but we all knew that the Russian economy was vulnerable, that it was a petro-state which had been a haven for crony capitalism… Russia had not invested in developing new industries or new institutions, but had focused solely on military expenditure. I have to say, the fact that I can stand here and speak these words without fear of being poisoned (glances nervously at the Russian diplomats in the room) is a testament to the fundamental changes that have been going on ever since in Russian society. In any case, investment in Russian companies by the Arctic states was completely brought to a halt. And so, Russia, unlike ever before, started struggling with skyrocketing national debt. Due to Russia’s extreme increase in military spending, in anticipation of securing revenues from unexploited Arctic resources, it had quickly ran through its accumulated reserves, and then steadily racked up national debt which got close to 80% of its GDP.

My sector, the fishing sector, was also hit hard by these developments. The Russian government could no longer afford to subsidise the large and overextended Russian fishing fleet and without state support it fragmented and splintered. To make things worse, China came in to repossess the assets it had invested in. Unemployment, soaring inflation and loss of confidence in the banking system put huge pressure on the government, which struggled to manage the situation. As we know, the Russian Federation was finally backed into a corner and sought rescue from the newly green-tinged International Monetary Fund, granted of course only under stringent conditions. Russia was not only forced into beginning a process of fundamental economic transformation, but also to stop and even reverse its military build-up in the Arctic. Now, that weaponized icebreaker which I spoke about is part of the same outdoor museum in Murmansk as the Lenin, the soviet nuclear powered icebreaker, that was launched during another period of extreme hubris, in 1957.

At just about this time, I had worked my way up to become CEO of Sakha Fishing, and struggled to steer my company through the mounting financial pressure and increasing illegal fishing as still more vessels moved into the Arctic. In all this turmoil, the Indigenous Peoples Secretariat had remained united, hosting annual meetings to voice indigenous peoples’ rights in the Arctic. I attended because I had hoped that with the Russian economic meltdown, the chaos in the fishing industry and the new reality of climate change, new Yakut business opportunities would be part of those discussions. Amazingly, already in that first, long meeting, we discussed a pan-Arctic indigenous-business alliance ‘Polar Renaissance’, which would be supported by the Secretariat as part of a larger reconciliation process. With Polar Renaissance and the Secretariat, we negotiated for Norway, Canada and Sweden to create a joint Arctic trust fund supporting indigenous-led transformation initiatives in the entire Arctic, including business, as part of a climate reparations agreement. This transformed the living conditions and future prospects not only for many Russian indigenous people, but indigenous communities all over the Arctic. It ultimately set off the ongoing institutional transformation we see today.

Now we are celebrating the fifth anniversary of our first Arctic Reconciliation meeting. At that meeting, we recognized our common history, highlighted current achievements and created a vision for the next 50 years based on our shared humanity and our desire to secure and nourish our collective wellbeing. We are working towards the ratification of the Arctic Treaty that Russia is now also part of. As part of the Arctic treaty negotiations, we hope to not only set up a body to manage our fisheries, overseeing all the high seas of the Arctic Ocean, but make sustainability performance and corporate social performance with respect to indigenous communities an obligation for ALL enterprises operating in the Arctic. Collectively, we are building towards a better future together, but in recognition of our 150 year vision, we also need to recognize the new challenges that continue to emerge. For my own industry, mercury, trapped for thousands of years in permafrost, is a serious threat, slowly seeping into our Arctic foodwebs. The Arctic has changed and will continue to change. But, with a united Arctic, we stand a chance. Thank you all for listening.

alternative pathway(s)

Tensions between the States become even more strained due to two issues. First, growing ship traffic along the Northern Sea Route causes force-on-force situations along the straits. Russia and Canada are on one side of the issue, and the USA and the EU on the other side. The straits issue becomes another source of interstate conflict in the region, as the two sides hold widely different views on the legal status of the waterways. Second, the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard (where a large part of the population is Russian), its surrounding continental shelf and Fisheries Protection Zone becomes a source for Norway-Russia conflict.

A major oil spill north of Siberia occurs either due to a tanker collision, a blowout on an offshore installation or a rupture in a pipeline. Given the vulnerability of the Arctic marine environment, this effectively puts an end to commercial fishing in large parts of the region.